¶ The Hallmarks of Aging

¶ Overview

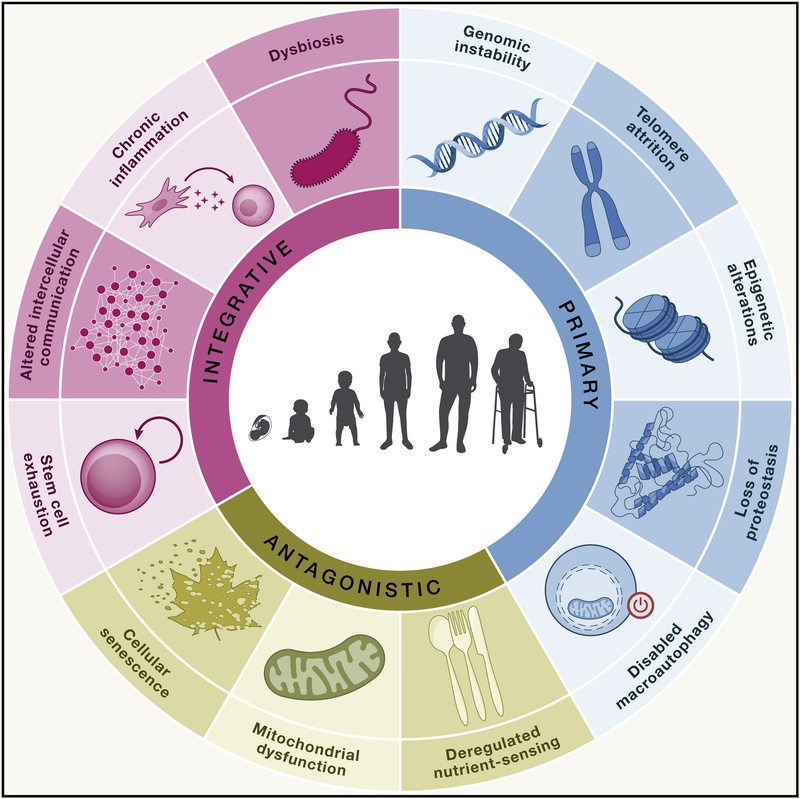

The Hallmarks of Aging is the definitive scientific framework for understanding the biological mechanisms that drive the aging process. Originally proposed in a landmark 2013 paper by López-Otín et al., the framework initially defined nine hallmarks. In 2023, a major update was published in Cell, expanding the universe of aging hallmarks to twelve distinct, interconnected processes[1][2].

These hallmarks provide a common language for aging research and identify specific targets for interventions to extend healthspan and lifespan.

Figure 1: The 12 Hallmarks of Aging, categorized into Primary, Antagonistic, and Integrative groups. Adapted from López-Otín et al. (2023).

¶ Evolution of the Framework

The original 2013 classification established aging research as a rigorous molecular discipline. The 2023 update incorporates a decade of new discoveries, adding three new hallmarks: Disabled Macroautophagy, Chronic Inflammation, and Dysbiosis[1:1].

¶ Criteria for a Hallmark

For a biological process to qualify as a hallmark of aging, it must strictly satisfy three conditions[1:2]:

- Age-associated manifestation: The phenomenon must be observed during normal aging.

- Experimental acceleration: Experimentally intensifying the process must accelerate aging.

- Therapeutic potential: Therapeutic inhibition or amelioration of the process must retard normal aging.

¶ The 12 Hallmarks of Aging

The hallmarks are hierarchically organized into three categories: Primary (causes of damage), Antagonistic (responses to damage), and Integrative (culprits of the phenotype).

¶ Primary Hallmarks (Causes of Damage)

These are the initiating triggers of the aging process, characterized by the accumulation of cellular damage.

¶ 1. Genomic Instability

Aging is accompanied by an accumulation of genetic damage throughout life. This includes somatic mutations, chromosomal aneuploidies, and copy number variations. Sources of damage include external agents (UV, radiation) and internal threats (ROS, replication errors). Deficiencies in DNA repair mechanisms (like NER, BER, and DSB repair) accelerate aging, as seen in progeroid syndromes like Werner syndrome[1:3][2:1].

¶ 2. Telomere Attrition

Telomeres are the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. Due to the "end-replication problem," telomeres shorten with each cell division. When they reach a critical length, cells enter senescence or apoptosis. Telomerase deficiency is linked to premature aging diseases (dyskeratosis congenita), while telomerase activation can delay aging in mice[1:4].

¶ 3. Epigenetic Alterations

Aging involves changes in the epigenetic landscape—modifications to DNA and histones that regulate gene expression without altering the sequence. Key changes include global DNA hypomethylation, focal hypermethylation at CpG islands, and histone modification imbalances (e.g., increase in H4K20me3, decrease in H3K9me3). These alterations lead to transcriptional noise and aberrant gene expression[1:5][3].

¶ 4. Loss of Proteostasis

Proteostasis (protein homeostasis) ensures the correct folding and clearance of proteins. Aging impairs the proteostasis network, leading to the accumulation of misfolded or aggregated proteins (e.g., amyloid-beta, tau). Key mechanisms include chaperone failure and dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome system[1:6][4].

¶ 5. Disabled Macroautophagy (New in 2023)

Macroautophagy is the primary mechanism for recycling damaged organelles and cytoplasmic content. While originally subsumed under proteostasis, it is now a distinct hallmark. Autophagy declines with age, leading to the accumulation of "cellular trash" (lipofuscin, damaged mitochondria). Enhancing autophagy (e.g., via rapamycin or spermidine) consistently extends lifespan in model organisms[1:7][5].

¶ Antagonistic Hallmarks (Responses to Damage)

These hallmarks typically begin as protective responses to primary damage but become deleterious when they become chronic or exacerbated.

¶ 6. Deregulated Nutrient Sensing

The network of nutrient-sensing pathways—including mTOR, AMPK, Sirtuins, and IGF-1—regulates cell growth and metabolism. In aging, the anabolic (growth) signaling (mTOR/IGF-1) is often overactive, while catabolic (repair) signaling (AMPK/Sirtuins) declines. Caloric restriction and mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin) are among the most robust longevity interventions known[1:8][6].

¶ 7. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria generate energy (ATP) but also produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). Aging leads to a decline in mitochondrial efficiency, reduced biogenesis, and accumulation of mutations in mtDNA. The 2023 update emphasizes that ROS are not strictly deleterious but act as signaling molecules (mitohormesis); dysfunction arises when this signaling is disrupted or when mitochondrial quality control (mitophagy) fails[1:9].

¶ 8. Cellular Senescence

Senescence is a state of stable cell cycle arrest induced by stress (e.g., DNA damage, telomere shortening). While essential for tumor suppression and wound healing, the accumulation of senescent cells in aged tissues drives pathology via the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP)—a cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteases that damages neighboring tissue[1:10][7].

¶ Integrative Hallmarks (Culprits of the Phenotype)

These hallmarks arise when the accumulated damage and antagonistic responses overwhelm tissue homeostasis, leading to functional decline.

¶ 9. Stem Cell Exhaustion

The regenerative potential of tissues declines with age due to the depletion or dysfunction of adult stem cells. This is driven by all upstream hallmarks (e.g., DNA damage in hematopoietic stem cells, senescence in satellite cells). The result is a failure of tissue maintenance and repair, contributing to anemia, sarcopenia, and immunosenescence[1:11].

¶ 10. Altered Intercellular Communication

Aging disrupts the communication signals between cells (endocrine, paracrine, and neuronal). This leads to a "noisy" systemic environment characterized by chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and defects in the neuro-endocrine-immune network. Strategies like parabiosis (young blood exchange) suggest that restoring youthful signaling factors can rejuvenate aged tissues[1:12].

¶ 11. Chronic Inflammation (New in 2023)

Often termed "inflammaging," this is a sterile, low-grade, persistent inflammation that accumulates with age. Unlike acute inflammation (a defense response), chronic inflammation causes systemic tissue damage. It is driven by the SASP from senescent cells, cell debris (DAMPs), and immune system dysregulation (immunosenescence). It is a key driver of multimorbidity, including cardiovascular disease and neurodegeneration[1:13][8].

¶ 12. Dysbiosis (New in 2023)

The gut microbiome undergoes significant changes during aging, losing diversity and shifting toward a pro-inflammatory profile (e.g., increase in Proteobacteria). This "dysbiosis" compromises the intestinal barrier ("leaky gut"), allowing bacterial products to enter circulation and trigger systemic inflammation. Restoring a youthful microbiome (e.g., via fecal transplant or probiotics) can extend lifespan in models like killifish[1:14][9].

¶ Interconnectedness and Therapeutics

The hallmarks are not isolated silos but a complex, interacting network. For instance:

- Genomic instability can trigger cellular senescence.

- Senescence produces SASP, driving chronic inflammation.

- Inflammation impairs stem cell function.

- Disabled autophagy prevents the clearance of damaged mitochondria (mitophagy failure), leading to further inflammation (inflammasome activation).

This interconnectivity implies that targeting one hallmark often impacts others. For example, senolytics (clearing senescent cells) not only reduce senescence but also lower chronic inflammation and improve stem cell function[1:15].

¶ References

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2023). Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell, 186(2), 243-278. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.001 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194-1217. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 ↩︎ ↩︎

Sen, P., Shah, P. P., Nativio, R., & Berger, S. L. (2016). Epigenetic mechanisms of longevity and aging. Cell, 166(4), 822-839. ↩︎

Kaushik, S., & Cuervo, A. M. (2015). Proteostasis and aging. Nature Medicine, 21(12), 1406-1415. ↩︎

Hansen, M., Rubinsztein, D. C., & Walker, D. W. (2018). Autophagy as a promoter of longevity: insights from model organisms. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 19(9), 579-593. ↩︎

Fontana, L., & Partridge, L. (2015). Promoting health and longevity through diet: from model organisms to humans. Cell, 161(1), 106-118. ↩︎

Gorgoulis, V., et al. (2019). Cellular senescence: defining a path forward. Cell, 179(4), 813-827. ↩︎

Franceschi, C., & Campisi, J. (2014). Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 69(Suppl_1), S4-S9. ↩︎

Ralli, C., et al. (2022). The gut microbiome and healthy aging. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. ↩︎