¶ Sauna and Heat Therapy: The Science of Passive Cardio

¶ At a Glance

What is it?

Sauna bathing is a form of whole-body thermotherapy that exposes the body to high heat (typically 80°C–100°C) for short durations. While often viewed as relaxation, it is a potent biological stressor that triggers powerful adaptive responses known as hormesis.

Why do it?

Regular sauna use acts as a "passive cardiovascular workout," reducing the risk of heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality by up to 40% [1][2]. It activates Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs), repairs damaged proteins, and stimulates autophagy (cellular cleanup).

Key Protocol

For maximum longevity benefits: 175°F+ (80°C+) for 20 minutes, 4–7 times per week [1:1].

¶ The "Why": Benefits & Health Outcomes

¶ 1. Drastic Reduction in Cardiovascular Mortality

The most robust evidence comes from the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study (KIHD), which followed over 2,300 Finnish men for 20 years. The results were dose-dependent:

- Sudden Cardiac Death: 63% lower risk for those using sauna 4–7 times/week compared to 1 time/week [1:2].

- All-Cause Mortality: 40% lower risk for frequent users (4–7x/week) [1:3].

- Hypertension: 46% lower risk of developing high blood pressure [3].

¶ 2. Neuroprotection & Dementia Prevention

Heat stress may protect the brain. The same KIHD study found that men using the sauna 4–7 times per week had a 66% lower risk of dementia and a 65% lower risk of Alzheimer's disease compared to those using it once a week [4]. Improved vascular function and reduced inflammation are likely contributors.

¶ 3. Mood & Mental Health

Hyperthermia increases the production of dynorphins (which cool the body and can create a sense of dysphoria initially) followed by a rebound in beta-endorphins, leading to the "sauna high." It also increases Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which supports neuronal health and may alleviate symptoms of depression [5][6].

¶ Mechanisms of Action

¶ Hormesis and Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs)

Sauna is a classic example of hormesis—beneficial stress. The primary cellular response to heat is the upregulation of Heat Shock Proteins (specifically HSP70).

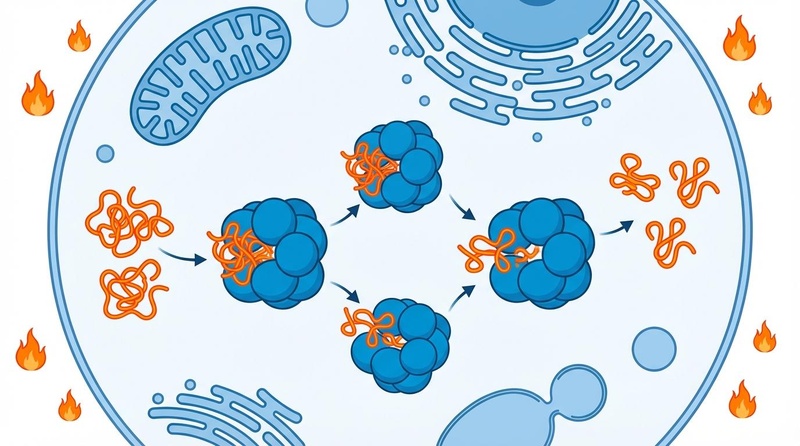

Figure 1: Under heat stress, Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) act as molecular chaperones, refolding misfolded proteins and preventing the toxic aggregation associated with aging and neurodegeneration.

- Chaperone Function: HSPs ensure that other proteins fold correctly and repair those that are damaged.

- Prevention of Aggregation: By maintaining proteostasis (protein balance), HSPs help prevent the accumulation of plaque (like beta-amyloid in Alzheimer's) [7].

- FOXO3 Activation: Heat stress activates the FOXO3 gene, a master regulator of longevity associated with DNA repair, stem cell maintenance, and immune function [8].

¶ Autophagy & Cellular Cleanup

Heat stress triggers autophagy, the body's internal recycling system. This process breaks down dysfunctional cellular components and clears out "molecular junk" [9].

- Protein Aggregate Clearance: Autophagy works alongside HSPs to degrade misfolded proteins that cannot be repaired.

- Mitochondrial Quality Control: Heat stress induces mitohormesis, where mild mitochondrial stress signals the cell to improve mitochondrial efficiency and biogenesis [10].

¶ Antioxidant Defense (Nrf2 Pathway)

Thermal stress activates the Nrf2 pathway, the "master switch" for antioxidant defense. Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and upregulates the production of endogenous antioxidants like glutathione, protecting cells from future oxidative stress [11].

¶ Cardiovascular Conditioning

- Endothelial Function: Heat improves the elasticity of blood vessels (compliance), lowering vascular resistance.

- Plasma Volume Expansion: Similar to endurance training, heat acclimation increases plasma volume, improving thermoregulation and cardiac stroke volume [12].

¶ Protocols: How to Sauna for Longevity

Not all sauna sessions are created equal. The clinical benefits cited in major studies are based on specific parameters.

¶ The "Finnish Gold Standard"

This protocol aligns with the data from the Laukkanen studies showing maximum mortality reduction.

| Parameter | Recommendation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Traditional Finnish (Dry/Steam) | Radiant heat; humidity can be added by throwing water on rocks ("löyly"). |

| Temperature | 176°F – 212°F (80°C – 100°C) | Lower temperatures may require longer durations for similar effects. |

| Duration | 15 – 20 minutes per session | Stay in until you feel a strong urge to cool down. |

| Frequency | 4 – 7 times per week | "More is better" up to daily use. 2-3x/week still provides benefit but less robustly. |

| Cool Down | Gradual or Cold Plunge | Combining with cold exposure (Nordic Cycle) may amplify metabolic effects but requires caution. |

¶ Infrared Saunas

Infrared (IR) saunas use light to heat the body directly rather than heating the air. They typically operate at lower temperatures (110°F – 140°F / 45°C – 60°C).

- Pros: More accessible for those who cannot tolerate high heat; deeply penetrating.

- Cons: Most longevity data is from high-heat Finnish saunas. To mimic the physiological strain of a Finnish sauna, you likely need to stay in an IR sauna significantly longer (30–45+ minutes) to achieve similar core body temperature elevation [13].

¶ Safety & Contraindications

While generally safe, heat stress places a significant load on the cardiovascular system.

¶ Who Should Avoid High-Heat Sauna?

- Unstable Heart Conditions: Unstable angina, recent myocardial infarction (within 6 weeks), or severe aortic stenosis [14].

- Pregnancy: Consult a physician; generally, avoiding extreme core temperature elevation is advised.

- Fever/Infection: Sauna increases metabolic demand and can worsen acute illness.

- Orthostatic Hypotension: Those prone to fainting should be cautious and exit slowly.

¶ Tips for Safety

- Hydrate: Drink water with electrolytes before and after. You can lose 0.5–1 liter of fluid in a session.

- Listen to Your Body: If you feel dizzy, nauseous, or uncomfortable, exit immediately. Hormesis requires mild stress, not suffering.

- Cool Down Gradually: Allow your heart rate to normalize before showering or entering a cold plunge.

¶ Comparisons

¶ Sauna vs. Steam Room

- Sauna: Low humidity (<20%), high heat (80°C+). Allows for sweat evaporation, making higher temps tolerable.

- Steam Room: High humidity (100%), lower heat (~45°C). Sweat does not evaporate, so the body heats up differently. While beneficial for respiratory health, there is less data connecting steam rooms to the specific longevity outcomes seen in Finnish sauna studies.

¶ Sauna vs. Hot Tub

- Hot water immersion also provides hydrostatic pressure and heat stress. It is effective for lowering blood pressure and improving sleep, but achieving the high core temperatures of a sauna (often required for maximal HSP activation) is more difficult and can be less comfortable for long durations [15].

¶ References

Laukkanen, T., Khan, H., Zaccardi, F., & Laukkanen, J. A. (2015). Association between sauna bathing and fatal cardiovascular and all-cause mortality events. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(4), 542–548. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2130724 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Laukkanen, J. A., Laukkanen, T., & Kunutsor, S. K. (2018). Cardiovascular and other health benefits of sauna bathing: a review of the evidence. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 93(8), 1111–1121. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(18)30275-1/fulltext ↩︎

Zaccardi, F., Laukkanen, T., Willeit, P., & Laukkanen, J. A. (2017). Sauna bathing and incident hypertension: a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Hypertension, 30(11), 1120–1125. https://academic.oup.com/ajh/article/30/11/1120/3867393 ↩︎

Laukkanen, T., Kunutsor, S., Kauhanen, J., & Laukkanen, J. A. (2017). Sauna bathing is inversely associated with dementia and Alzheimer's disease in middle-aged Finnish men. Age and Ageing, 46(2), 245–249. https://academic.oup.com/ageing/article/46/2/245/2654230 ↩︎

Janssen, C. W., Lowry, C. A., Mehl, M. R., et al. (2016). Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(8), 789–795. ↩︎

Kojima, D., Nakamura, T., Banno, M., et al. (2018). Head-out immersion in hot water increases serum BDNF in healthy humans. International Journal of Hyperthermia, 34(6), 834–839. ↩︎

Iguchi, M., Littmann, A. E., Chang, S. H., et al. (2012). Heat stress and cardiovascular, hormonal, and heat shock protein responses in humans. Journal of Athletic Training, 47(2), 184–190. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3418130/ ↩︎

Willcox, B. J., Donlon, T. A., He, Q., et al. (2008). FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(37), 13987–13992. ↩︎

Moore, M. N. (2020). Autophagy and Hormesis. Cells, 9(5), 1279. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7343375/ ↩︎

Ristow, M., & Schmeisser, K. (2014). Mitohormesis: Promoting Health and Lifespan by Increased Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Dose-Response, 12(2), 288-341. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4036400/ ↩︎

Zhang, D. D. (2024). Hormesis and polyphenol mediate Nrf2 regulation of disease and health. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Hormesis-and-polyphenol-mediate-Nrf2-regulation-of-disease-and-health-Heat-shock_fig3_382240492 ↩︎

Scoon, G. S., Hopkins, W. G., Mayhew, S., & Cotter, J. D. (2007). Effect of post-exercise sauna bathing on the endurance performance of competitive male runners. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 10(4), 259–262. ↩︎

Beever, R. (2009). Far-infrared saunas for treatment of cardiovascular risk factors: summary of published evidence. Canadian Family Physician, 55(7), 691–696. https://www.cfp.ca/content/55/7/691 ↩︎

Kukkonen-Harjula, K., & Kauppinen, K. (2006). Health effects and risks of sauna bathing. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 65(3), 195–205. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16871826/ ↩︎

Brunt, V. E., Howard, M. J., Francisco, M. A., et al. (2016). Passive heat therapy improves endothelial function, arterial stiffness and blood pressure in sedentary humans. Journal of Physiology, 594(18), 5329–5342. ↩︎