¶ Spermidine

Spermidine is a naturally occurring polyamine found in ribosomes and living tissues. It plays a critical role in cellular function and survival. In longevity science, it has gained prominence as a caloric restriction mimetic due to its ability to induce autophagy, the body's cellular cleanup process. While animal studies consistently show that spermidine supplementation extends lifespan and delays age-related diseases, human clinical trials have produced mixed results, highlighting the importance of dosage and formulation.

¶ Mechanism of Action

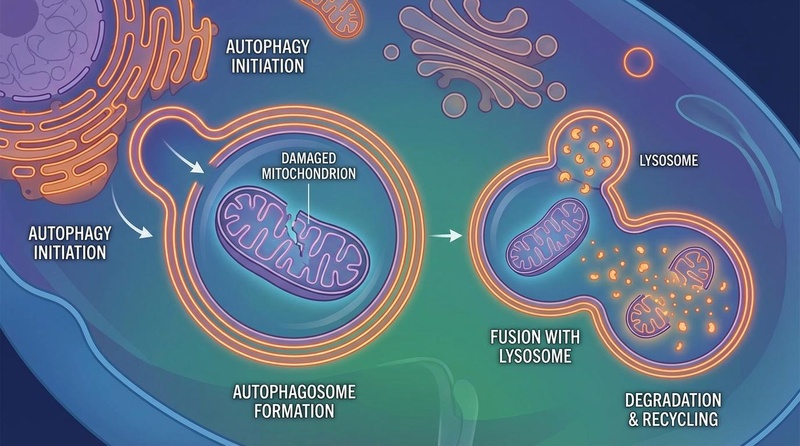

Spermidine functions as a caloric restriction mimetic, inducing autophagy—the cellular "cleanup" process where autophagosomes engulf and recycle damaged organelles like mitochondria.

Spermidine exerts its anti-aging effects primarily through the maintenance of proteostasis and mitochondrial quality control. Its mechanisms are deeply intertwined with the Hallmarks of Aging.

¶ Autophagy Induction

The most well-established mechanism of spermidine is the induction of macroautophagy (often just called autophagy). It achieves this via two main pathways:

- EP300 Inhibition: Spermidine competitively inhibits EP300 (E1A-associated protein p300), an acetyltransferase that normally suppresses autophagy. By inhibiting EP300, spermidine promotes the deacetylation of key autophagy-related proteins (such as Atg5, Atg7, and LC3), thereby activating them[1][2].

- Transcriptional Activation: The inhibition of EP300 also leads to the deacetylation of histone H3, which upregulates the transcription of autophagy-related genes (Atg genes)[3][4].

This process helps reverse Disabled Macroautophagy and clears cellular debris such as lipofuscin and damaged organelles.

¶ The eIF5A-TFEB Axis

Spermidine is the essential substrate for the hypusination of eIF5A (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A). Hypusinated eIF5A is critical for the translation of TFEB (Transcription Factor EB), a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis. By restoring eIF5A hypusination, spermidine enhances lysosomal function and cellular cleanup, which is particularly relevant for immune system aging[5][6].

¶ Other Mechanisms

- Mitochondrial Health: Spermidine promotes mitophagy (the selective degradation of damaged mitochondria), addressing Mitochondrial Dysfunction[7].

- Anti-Inflammatory: Through autophagy and other pathways, it helps reduce systemic inflammation, potentially impacting Inflammaging.

- Epigenetic Regulation: As an inhibitor of histone acetyltransferases (HATs), it directly influences Epigenetic Alterations[4:1].

¶ Clinical Evidence

While preclinical data is robust, human evidence is evolving, with some trials showing promise and others finding no benefit at standard doses.

¶ Cognition and Memory

- Evidence Level: Low to Moderate

- Direction: Mixed/Dose-Dependent

The SmartAge Trial (2022), a rigorous 12-month double-blind RCT with 100 participants, investigated the effects of 0.9 mg/day of spermidine. The study found no significant improvement in the primary endpoint (mnemonic discrimination) compared to placebo. However, exploratory analyses suggested potential modest benefits in verbal memory and reduced inflammation[8][9].

In contrast, a study involving nursing home residents reported cognitive benefits at a significantly higher dose of 3.3 mg/day, suggesting that the effects of spermidine on cognition may be dose-dependent and that standard low-dose supplements might be insufficient for noticeable cognitive enhancement[10].

¶ Cardiovascular Health

- Evidence Level: Low (Observational)

- Direction: Positive

Epidemiological data strongly links dietary spermidine intake to cardiovascular longevity. The Bruneck Study, a prospective cohort study following 829 individuals for 20 years, found that those with high dietary spermidine intake had reduced blood pressure and a ~40% lower risk of fatal heart failure[11].

Similarly, an analysis of NHANES data (2003-2014) in the U.S. population associated higher spermidine intake with reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality[12]. While these associations are strong, large-scale RCTs are needed to confirm causality.

¶ Immune Function

- Evidence Level: Very Low

- Direction: Positive (Mechanistic)

Mechanistic studies indicate that spermidine can restore the eIF5A-TFEB axis in aged B-cells, improving antibody production ex vivo[5:1]. Small human trials using spermidine blends have hinted at immune benefits, but isolation of spermidine's specific contribution remains difficult[13].

¶ Food Sources

Common dietary sources rich in spermidine include wheat germ, soybeans, and aged cheese.

Spermidine is present in a wide variety of foods, with concentrations heavily influenced by processing, fermentation, and storage.

| Food Source | Content (mg/kg) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat Germ | 243 – 350 | The richest natural source and the basis for most supplements[14][15]. |

| Soybeans (Dried) | 165 – 291 | Highly variable; fermentation (e.g., Natto) generally enhances bioavailability[14:1]. |

| Aged Cheese | 20 – 82 | Content increases with aging duration (e.g., Cheddar, Parmesan, Gouda)[16]. |

| Mushrooms | 67 – 124 | Certain varieties like Black Shimeji are notably high[17]. |

| Chicken Liver | 32 – 161 | The highest animal-based source[14:2]. |

| Green Peas | ~50 | A good plant-based source (approx. 8 mg per cup)[14:3]. |

| Natto | 65 – 340 | Fermented soybeans; concentrations vary by brand and fermentation time[17:1]. |

¶ Safety and Dosage

¶ Safety Profile

Spermidine has an excellent safety profile. It is a naturally occurring compound in the human body and in food.

- Standard Doses: Clinical trials lasting up to 12 months (at 0.9 mg/day) reported no significant adverse events compared to placebo[8:1].

- High Doses: A 2024 safety trial confirmed that doses as high as 40 mg/day for 28 days were well-tolerated in healthy older men, with no changes in vital signs or clinical chemistry[18].

- Regulatory Status: Wheat germ extracts rich in spermidine are Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS).

¶ Dosage

- Dietary Intake: The average Western diet provides about 10 mg/day, while a Mediterranean diet (rich in plants and whole grains) provides 15–25 mg/day[19].

- Supplementation: Standard supplements typically provide 1 mg – 6 mg/day, usually derived from wheat germ extract.

- Pharmacokinetics: Interestingly, supplementation leads to a more significant increase in plasma spermine (a downstream metabolite) than spermidine itself, suggesting tight homeostatic regulation of polyamine levels in the blood[2:1][18:1].

¶ Interactions

There are no well-documented drug interactions in major medical databases. However, because spermidine induces autophagy, patients on complex medication regimens or those with active cancer should consult a healthcare provider, as autophagy can play a dual role in cancer progression (suppressing initiation but potentially supporting established tumors).

¶ References

Pietrocola, F., et al. (2015). Spermidine induces autophagy by inhibiting the acetyltransferase EP300. Cell Death & Differentiation. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4326581/ ↩︎

High-Dose Spermidine Supplementation Does Not Increase Plasma Spermidine Levels. (2023). Nutrients. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10143675/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Madeo, F., et al. (2018). Spermidine delays aging in humans. Science. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6287690/ ↩︎

Madeo, F., et al. (2018). Spermidine in health and disease. Science. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6128428/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Zhang, H., et al. (2019). Polyamines control eIF5A hypusination, TFEB translation, and autophagy to reverse B cell senescence. Autophagy. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15548627.2019.1698210 ↩︎ ↩︎

Zhang, H., et al. (2019). eIF5A promotes translation of TFEB to regulate autophagy and mitochondrial function. Molecular Cell. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6863385/ ↩︎

MDPI. (2024). Antioxidants and Spermidine. Antioxidants. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/13/12/1482 ↩︎

Schwarz, C., et al. (2022). Safety and tolerability of spermidine supplementation in mice and older adults with subjective cognitive decline. JAMA Network Open. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35616942/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Schwarz, C., et al. (2022). Effects of spermidine supplementation on cognition and biomarkers in older adults with subjective cognitive decline: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9136623/ ↩︎

Pekar, T., et al. (2021). The effect of spermidine-rich wheat germ extract on cognitive function. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33211152/ ↩︎

Eisenberg, T., et al. (2016). Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nature Medicine. https://www.scribd.com/document/965292219/Eisenberg-2016 ↩︎

Association between dietary spermidine and all-cause mortality: Evidence from NHANES. (2022). Frontiers in Public Health. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.949170/full ↩︎

Human Supplementation with AM3... (2024). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11591374/ ↩︎

Jiabei Supplement. (2025). Spermidine foods. https://www.jiabeisupplement.com/spermidine-foods-for-longevity-and-health/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Purovitalis. (2025). Foods high in spermidine: The complete list. https://purovitalis.com/foods-high-in-spermidine-the-complete-list/ ↩︎

Lee, H., et al. (2021). Polyamine Content in Common Foods. Foods. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7824754/ ↩︎

New Phase Blends. (2025). Foods that contain spermidine. https://www.newphaseblends.com/foods-contain-spermidine/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Chrysea Labs. (2024). Safety of high-dose spermidine. Nutrition Research. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39405978/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Chrysea Labs. (2024). Dietary intake of spermidine. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384170048 ↩︎